New findings from the Gaia Space Telescope suggest that the Milky Way may have eaten a young galaxy not long ago, in cosmic terms. In fact, the last major collision between our galaxy and another galaxy appears to have occurred Billions Years later than previously expected.

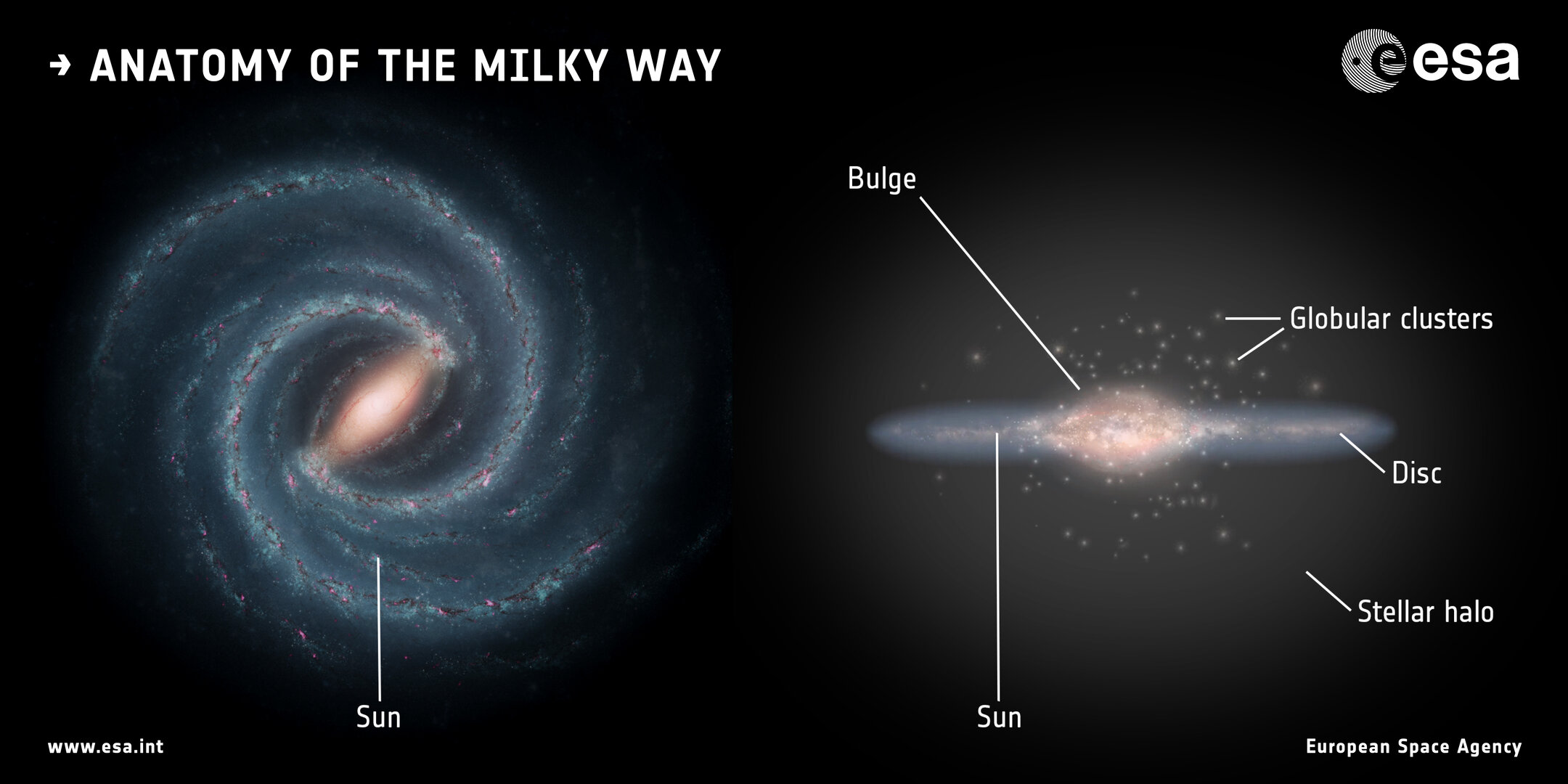

The Milky Way has long been known to have grown through a series of violent collisions, which tore apart small galaxies due to the massive gravitational influence of our solar system’s spiral home. These collisions distribute stars from the devouring galaxy across the halo surrounding the Milky Way’s main disk and its distinctive spiral arms. These bouts of galactic cannibalism also send “wrinkles” rippling across the Milky Way and affecting different “families” of stars, of different origins, in different ways.

With its ability to precisely pinpoint the position and motion of more than 100,000 local stars in the solar system within the entire catalog of stellar objects in the displays, Gaia aims to retell the history of the Milky Way by counting its wrinkles.

Related: In the Milky Way, there are 3 intruder stars that are “on the run” – in the wrong direction

“We get wrinklier as we age, but our work reveals that the opposite is true for the Milky Way,” says Thomas Donlon, study team leader at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and University. “It’s a kind of Benjamin Button universe, which becomes less wrinkly as we age.” the time”. alabama world, He said in a statement. “By looking at how these wrinkles dissipate over time, we can track when the Milky Way experienced its last major crash — and it turns out this happened billions of years later than we thought.”

These galactic wrinkles were only discovered by Gaia in 2018; This is the first time that extensive research has been conducted to uncover the timing of the collision that led to their appearance.

The halo of stars moves in strange ways

Our galaxy’s halo is full of stars with strange orbits, many of which are thought to be the “remnants” of galaxies that were once gobbled up by the Milky Way.

Many of those stars are thought to be the debris of what is called a “last major merger,” referring to the last time the Milky Way experienced a major collision with another galaxy. Scientists believe this recent major collision may have involved a massive dwarf galaxy, and the event is known as the Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus Merger (GSE). It is believed to have filled the Milky Way with stars in orbits that brought it close to the galactic center. The GSE is thought to have occurred between eight and 11 billion years ago when the Milky Way was in its infancy.

Since 2020, Thomas and his team have been comparing the Milky Way’s wrinkles to simulations of how these galactic collisions and mergers might appear. However, Gaia’s observations of these strangely orbiting stars — released as part of the space telescope’s Data Release 3 in 2022 — suggest that these strange stellar objects could have been deposited by a different merger event.

“We can see how the shapes and number of wrinkles change over time using these simulated mergers. This allows us to pinpoint the exact time when the simulation best matches what we see in real Gaia data for the Milky Way today — a method we used in this new study,” Donlon explained. Also, “By doing this, we found that the wrinkles were most likely caused by a dwarf galaxy colliding with the Milky Way about 2.7 billion years ago. We called this event the “Virgin radial merger.”

“For star wrinkles to be as pronounced as they appear in the Gaia data, they must have joined us less than three billion years ago — at least five billion years later than previously thought,” said team member Heidi Jo Newberg, also of Rensselaer. Polytechnic Institute said. “New star wrinkles form every time stars swing back and forth across the center of the Milky Way. If they joined us eight billion years ago, there would be so many wrinkles next to each other that we would no longer be able to see them as separate features.”

Recent examination of the Gaia observations calls into question whether a massive ancient merger in the early history of the Milky Way was really needed to explain the strange orbits of some stars in the galaxy. It also casts doubt on all the stars previously linked to the GSE merger.

“This finding — that a significant portion of the Milky Way only joined us within the last few billion years — represents a major change from what astronomers have thought until now,” Donlon said. “Many models and popular ideas about how the Milky Way grows predict that a recent direct collision with a dwarf galaxy of this mass would be very rare.”

The team also believes that the Virgo radial merger brought into our galaxy a family of other small dwarf galaxies and star clusters, which could have been gobbled up by the Milky Way at around the same time.

Future investigation and data from Gaia could show whether any objects previously associated with the GSE event are indeed associated with the more recent Virgo Radial Merger.

This new research is the latest in a trove of findings emerging from Gaia data that are rewriting the history of the Milky Way.

This cosmic review was made possible by Gaia’s unique ability to explore a large number of stars above Earth, allowing the space telescope to compile an unparalleled map of the positions, distances and movements of about 1.5 billion stars to date.

“The history of the Milky Way is constantly being rewritten, thanks to new data from Gaia,” Donlon concluded. “Our picture of the Milky Way’s past has changed dramatically from a decade ago, and I believe our understanding of these mergers will continue to change rapidly.”

The team’s research was published in May the magazine Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“Typical beer advocate. Future teen idol. Unapologetic tv practitioner. Music trailblazer.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

How did black holes get so big and so fast? The answer lies in the darkness

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin