It’s easy to think of Earth as a watery world, with its vast oceans and beautiful lakes, but compared to many worlds, Earth is particularly wet. Even the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn have much more liquid water than Earth. Earth is unusual not because it has liquid water but because it has liquid water in the Sun’s warm, habitable zone. As a new study in Nature Communications It shows that the Earth could be much stranger than we thought.

Water is one of the most common molecules in the universe. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, and oxygen is readily produced as part of the stellar CNO fusion cycle. So we would expect water-rich planets to be abundant in star systems. But this does not mean that liquid water will be abundant. In our solar system, there are two worlds with liquid water. Giant satellites of Earth and gas.

Like other warm terrestrial planets such as Venus and Mars, the Earth had liquid water in its youth. Mars was too young to hold its water. Much of it evaporated into space, while some froze in its surface crust. Venus was big enough to hold water, but its intense heat caused much of it to boil away in its thick atmosphere. We’re still not quite sure how Earth manages to retain its oceans, but it’s likely a combination of a strong magnetic field and extra help from water from asteroids and comets during a period of heavy bombardment.

The icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn are another story. It was far enough from the Sun that it retained the water of its formation. They quickly formed a thick layer of ice to prevent water from evaporating into space. But these moons are small worlds and would have frozen very quickly were it not for the tidal forces exerted by their gas giants.

Since cold gas planets are likely to have icy moons, the general idea is that we are more likely to find life in a world similar to Europa than in a world similar to Earth. But this new study calls for a difference. He argues that liquid water is more likely to exist on super-Earths.

The number of exoplanets discovered by the Kepler mission as of May 2016.

Credit: W. Stenzel/NASA Ames

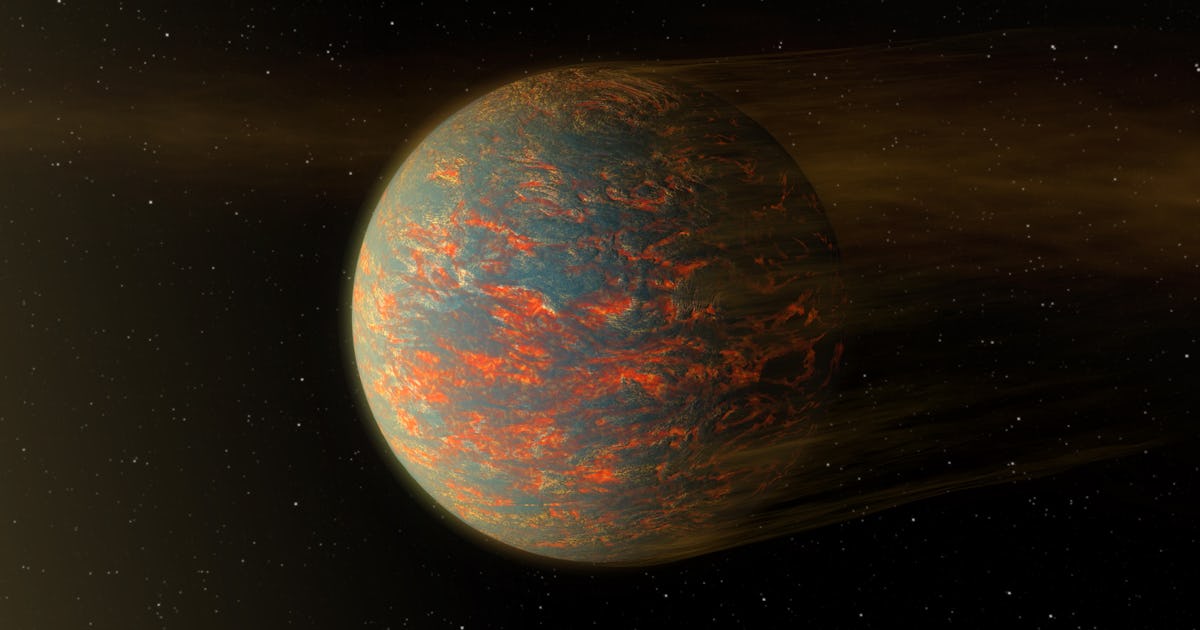

The super-Earths span a mass range from a couple of Earth masses to that of Neptune. At the big end are likely gaseous worlds with dense atmospheres. On the small end, they’ll likely be more Earth-like. Based on the exoplanets we’ve found so far, super-Earths are by far the most common. Most of them are likely to be outside the habitable zone of their stars in the cooler regions of the star system. So it is likely to be rich in water. But it’s also unlikely to be found orbiting a gas giant, so it’s generally assumed that the ice sheet will mostly freeze solid over time.

The reason has to do with the different freezing and melting points of ice. The type of ice on Earth melts at about 0°C. But this is only true about Earth’s atmospheric pressure. At high pressure, there are several types of ice with different melting points. Although it is a bit complex, at higher pressures, ice can have a much higher melting point. So even if the super-Earth is geologically active, it may not be warm enough to melt the ice.

This new study shows that super-Earths don’t have to be hot enough to form a deep ocean. Through geothermal and nuclear heating, it can melt a thin layer of water on its surface, and thanks to cracks and various water phase transitions, water can infiltrate the layer just below the frozen surface. This process would be enough to create a rich layer of liquid water for the oceans. Because the giant Earth’s heat lasts billions of years, it can maintain a liquid ocean long enough for life to evolve.

Based on what we know about exoplanets, oceans of giant Earths could be 100 times more common than those of Earth-like worlds or icy moons. This means that life has more possible homes than we thought.

This article was originally published the universe today by Brian Cooperlin. Read the The original article is here.

“Typical beer advocate. Future teen idol. Unapologetic tv practitioner. Music trailblazer.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

How did black holes get so big and so fast? The answer lies in the darkness

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin