University College London

University College LondonA group of Scottish islands may help solve one of our planet’s greatest mysteries, scientists say.

Researchers have discovered that the Garvelash Islands off the west coast of Scotland are the best record of Earth entering its largest ever ice age about 720 million years ago.

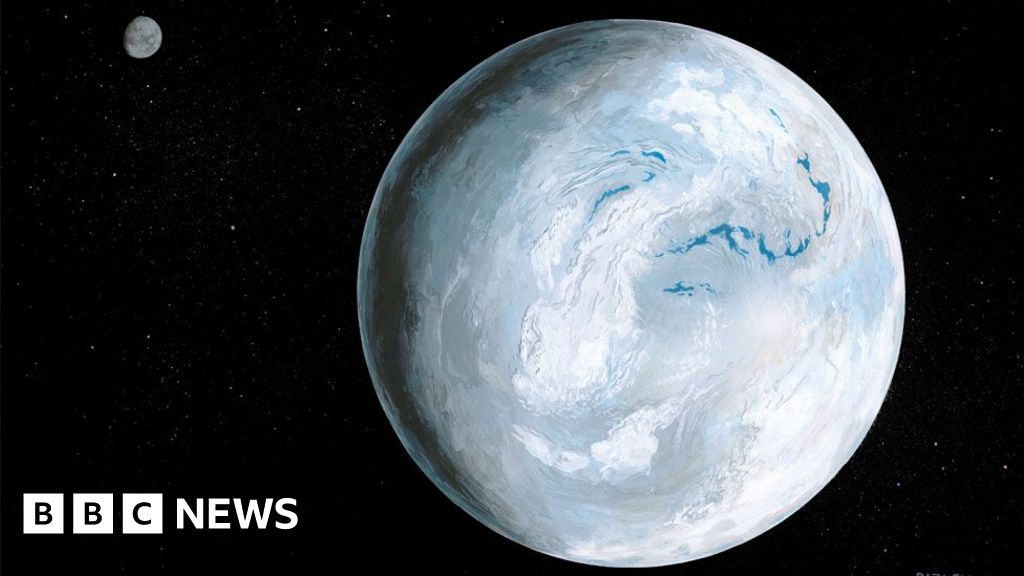

The Great Freeze, which covered almost the entire globe in two stages for 80 million years, is known as the “Snowball Earth”, after which the first animal life arose.

Evidence of glaciation hidden in rocks has been wiped out everywhere—except on the Garvelash Islands. Researchers hope the islands will tell us why Earth was frozen in a deep, icy state for so long and why complex life was necessary.

English:SPL

English:SPLRock layers can be thought of as pages in a history book – each layer contains details of the state of the Earth in the distant past.

But it was thought that the critical period before Snowball Earth was missing because the rock layers were eroded by the Great Freeze.

Now a new study by researchers at University College London has revealed that the Garvelash region somehow survived the catastrophe. It may be the only place on Earth that contains a detailed record of how the Earth entered one of the most catastrophic periods in its history – as well as what happened when the first animal life appeared as the Ice Ball melted hundreds of millions of years ago.

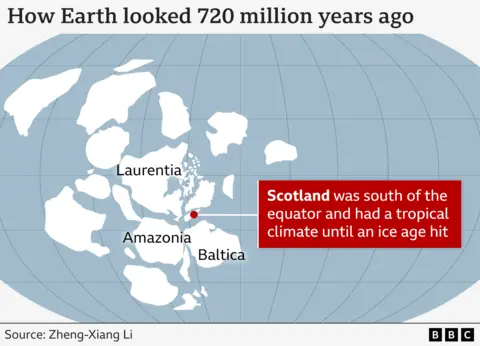

At that time Scotland was in a very different place because the continents had moved over time. It was south of the equator and had a tropical climate, until it and the rest of the planet were covered by ice.

“We have captured the moment when the Ice Age entered Scotland, which is missing from all other parts of the world,” Professor Graham Shields of University College London, who led the research, told BBC News.

“The critical millions of years are lost elsewhere due to glacial erosion – but they are all present in the rock layers in the Garvelash area.”

The islands in Scotland’s Inner Hebrides are uninhabited, except for a team of scientists working out of a secluded building on the main island, although there are ruins of a Celtic monastery dating back to the 6th century.

The discovery was made by PhD student Elias Rogin, whose findings were published in the Journal of the Geological Society of London. He is the first to date rock layers and identify them as belonging to a critical period that is absent from all other rock formations around the world.

His discovery puts the Garvilash family on a list of the biggest prizes in science: a golden nail hammered into sites identified as the best record of geological moments that changed the planet — though the nail is not actually made of gold to keep thieves away.

University College London

University College LondonElias has taken several Golden Spike judges, formally known as the “Cryogenian Subcommittee” members, to the rock faces several times to plead his case.

The next stage is to allow the wider geological community to voice any objections or come up with a better candidate. If there are no objections, the decision could be imposed next year.

This award will raise the scientific status of the site and attract more research funding.

If she wins the prize, she will please the man who first identified the importance of composition when he was a young researcher 60 years ago, Dr Tony Spencer.

“There are about 50 places we could have picked for this golden spike, but this is where the rocks are thicker and the sediments are more continuous,” he told BBC News.

“This appears to preserve the oldest point in time when there is a record of this particular ice age.”

“Typical beer advocate. Future teen idol. Unapologetic tv practitioner. Music trailblazer.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

How did black holes get so big and so fast? The answer lies in the darkness

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin