New research suggests that the last major collision in our galaxy occurred billions of years later than previously thought.

Using data from the Gaia spacecraft, researchers found that milky wayThe last major galactic collision occurred less than three billion years ago, not eight to eleven billion years ago as previously thought.

Heidi Jo Newberg, a professor of astronomy at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Tom Donlon, a visiting scholar at Rensselaer and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Alabama, and their team recently published a paper revealing a shocking discovery about the history of our universe: The Milky Way’s last major collision occurred billions of years later than previously thought.

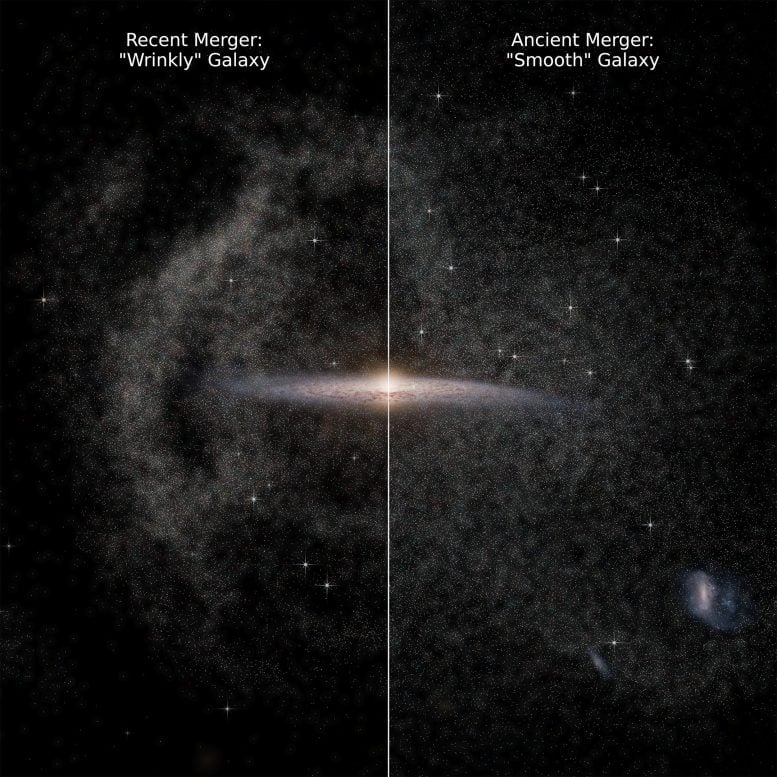

This discovery was made possible thanks to European Space AgencyNASA’s Gaia spacecraft, which is mapping more than a billion stars throughout the Milky Way and beyond, tracking their motion, brightness, temperature and composition. Newberg, a renowned astrophysicist and Milky Way expert, and Donlon focused on so-called “wrinkles” in our galaxy, which form when other galaxies collide with the Milky Way.

“We get more wrinkled as we age, but our work shows that the opposite is true for the Milky Way. It’s a sort of cosmic Benjamin Button figure that gets less wrinkled over time,” said Donlon, lead author of the new Gaia study, which was his doctoral thesis at Rensselaer. “By looking at how these wrinkles dissipate over time, we can track when the Milky Way last had its big crash — and it turns out that it happened billions of years later than we thought.”

Revised Hungarian Timetable

By comparing their observations of wrinkles with cosmological simulations, the team was able to determine that our last major collision with another galaxy did not actually occur eight to eleven billion years ago, as previously thought.

“For the star wrinkles to be as pronounced as they are in the Gaia data, they would have to have joined us at least three billion years ago—at least five billion years later than previously thought,” said Newberg, Donlon’s thesis advisor at Rensselaer. “New star wrinkles form every time the stars swing back and forth across the center of the Milky Way. If they had joined us eight billion years ago, there would have been so many wrinkles next to each other that we would no longer see them as separate features.”

Implications of the new results

The collision is thought to have created a large number of stars with unusual orbits. Previously, scientists estimated that it was between eight and 11 billion years ago in a collision called the Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus merger. But Newberg and Donlon’s findings suggest that the stars may have been created by the Virgo-Radio merger, which crashed into the center of the Milky Way less than three billion years ago.

“Gaia is a highly productive mission that is changing our view of the Universe,” says Dr Timo Prusti, Gaia Project Scientist at ESA. “Results like this are made possible by the incredible teamwork and collaboration of a large number of scientists and engineers across Europe and beyond.”

“With this study, Drs. Newberg and Donlon have made a stunning discovery about the history of the Milky Way,” said Dr. Curt Brenneman, dean of the College of Science. “Gaia data provide unprecedented opportunities to better understand our universe, and I am thrilled that the Rensselaer researchers were able to harness the power of this incredibly detailed new data.”

Reference: “The Wreckage of the ‘Last Big Merger’ Is Dynamically Young” by Thomas Donlon, Heidi Jo Newberg, Robin Sanderson, Emily Brigo, Danny Horta, Arpit Arora, and Nund Panthanpaisal, May 16, 2024, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stae1264

Newberg and Donlon are joined in the research by Dr. Robin Sanderson, of University of Pennsylvania The Flatiron Institute; Dr. Emily Brigo, Dr. Arpit Arora, and Dr. Nund Panthanpaisal of the University of Pennsylvania; and Dr. Danny Horta of the Flatiron Institute and the Astrophysical Research Institute.

“Typical beer advocate. Future teen idol. Unapologetic tv practitioner. Music trailblazer.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

How did black holes get so big and so fast? The answer lies in the darkness

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin