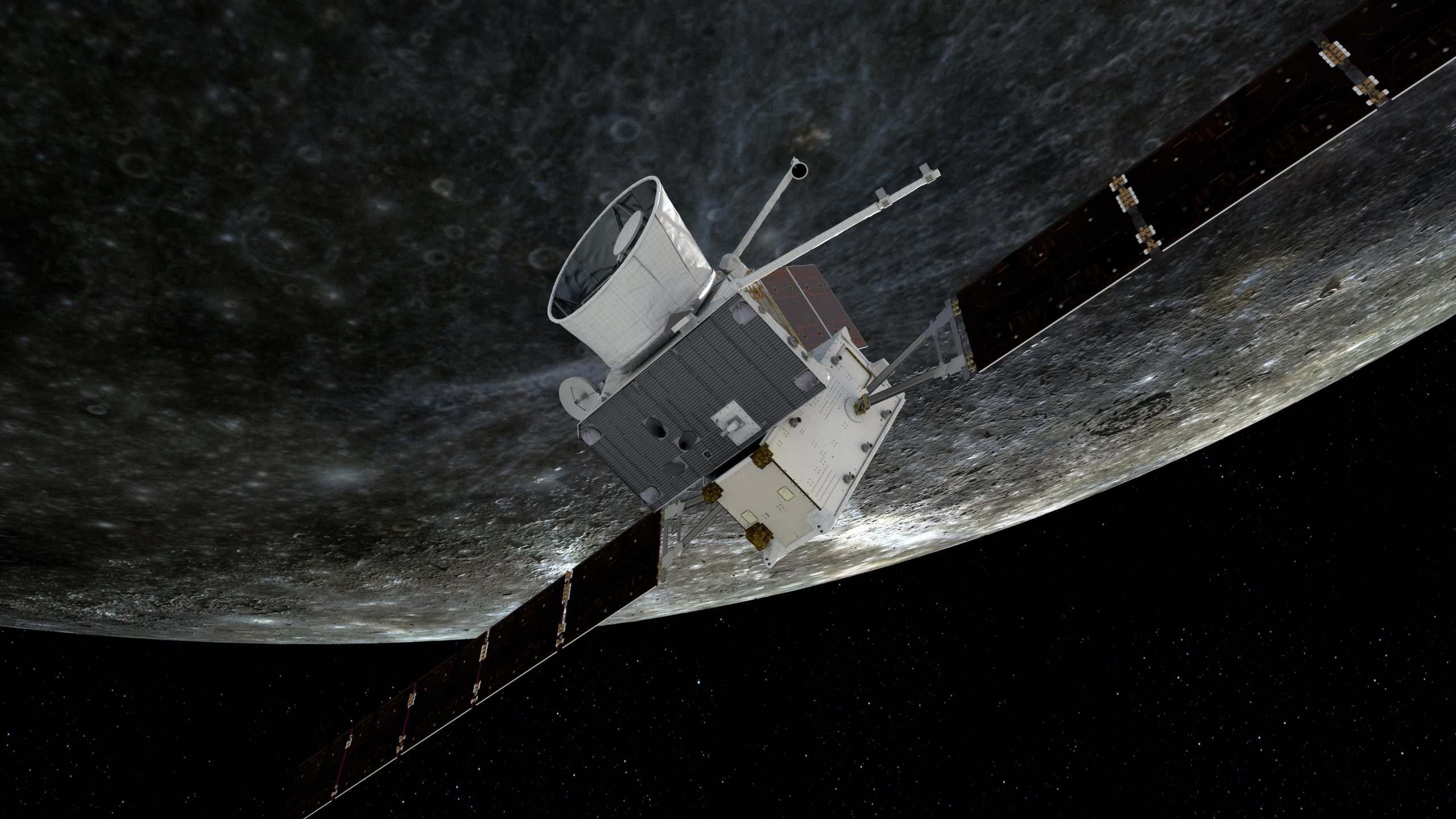

The European Space Agency/JAXA BepiColombo mission has successfully completed its third flyby of Mercury, capturing valuable images of geological features including the newly named Manley crater. Through continuous “thrust arcs,” the spacecraft is gradually adjusting its trajectory to enter Mercury’s orbit in 2025. The main science phase of the mission will launch in early 2026 after several more adjustments and another flyby in 2024. (Artistic impression of BepiColombo flying by Mercury. ) Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

European Space Agency /[{” attribute=””>JAXA BepiColombo mission has made its third of six gravity assist flybys at Mercury, snapping images of a newly named impact crater as well as tectonic and volcanic curiosities as it adjusts its trajectory for entering Mercury orbit in 2025.

The closest approach took place at 19:34 UTC (21:34 CEST) on June 19, 2023, about 236 km (147 miles) above the planet’s surface, on the night side of the planet.

“Everything went very smoothly with the flyby and images from the monitoring cameras taken during the close approach phase of the flyby have been transmitted to the ground,” says Ignacio Clerigo, ESA’s BepiColombo Spacecraft Operations Manager.

Some of the images acquired of Mercury by the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo spacecraft during its third Mercury flyby on June 19, 2023. Many geological features are visible, including the newly named Manley impact crater. The images were captured by the onboard monitoring cameras, which provide black-and-white snapshots in 1024 x 1024 pixel resolution. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

“While the next Mercury flyby isn’t until September 2024, there are still challenges to tackle in the intervening time: our next long solar electric propulsion ‘thruster arc’ is planned to start early August until mid-September. In combination with the flybys, the thruster arcs are critical in helping BepiColombo brake against the enormous gravitational pull of the Sun before we can enter orbit around Mercury.”

The Mercury Transfer Module of the BepiColombo mission is equipped with three monitoring cameras (M-CAM), which provide black-and-white snapshots in 1024 x 1024 pixel resolution. The positions of the three cameras are indicated with the orange icons, and example fields of view are illustrated. M-CAM 1 looks down the extended solar array of the MTM, while M-CAM 2 and 3 are looking toward the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO). The MPO’s medium-gain antenna and magnetometer boom can be seen in M-CAM 2, once deployed. M-CAM 3 has the possibility to see the MPO’s high-gain antenna. Since all deployable parts of the spacecraft are rotatable, a range of orientations may be seen in the actual images. Credit: ESA

Geological curiosities

During last night’s close encounter, monitoring camera 3 snapped tens of images of the rocky planet. The images, which provide black-and-white snapshots in 1024 x 1024 pixel resolution, were downloaded overnight until early this morning. Three ‘early release’ images are presented here.

Mercury starts appearing from the night side at the top right of this image taken by the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission on June 19, 2023, as the spacecraft sped by for its third of three gravity assist maneuvers at the planet. The image was taken at 19:49 UTC (21:49 CEST) by the Mercury Transfer Module’s monitoring camera 3, when the spacecraft was about 2536 km from the planet’s surface. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

Approaching on the nightside of the planet, a few features started to appear out of the shadows about 12 minutes following the closest approach, when BepiColombo was already about 1800 km (1100 miles) from the surface. The planet’s surface became more optimally illuminated for imaging from about 20 minutes after close approach and onwards, corresponding to a distance of about 3500 km (2200 miles) and beyond. In these closer images, a bounty of geological features are visible, including a newly named crater.

Annotated version of the image above. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

Crater named for artist Edna Manley

A large 218 km-wide peak-ring impact crater visible just below and to the right of the antenna in the two closest images presented here has just been assigned the name Manley by the International Astronomical Union’s Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature after Jamaican artist Edna Manley (1900–1987).

“During our image planning for the flyby we realized this large crater would be in view, but it didn’t yet have a name,” explains David Rothery, Professor of Planetary Geosciences at the UK’s Open University and a member of the BepiColombo MCAM imaging team. “It will clearly be of interest for BepiColombo scientists in the future because it has excavated dark ‘low reflectance material’ that may be remnants of Mercury’s early carbon-rich crust. In addition, the basin floor within its interior has been flooded by smooth lava, demonstrative of Mercury’s prolonged history of volcanic activity.”

A bounty of geological features, including the newly named Manley impact crater, are visible in this image of Mercury taken by the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission on June 19, 2023, as the spacecraft sped by for its third of three gravity assist maneuvers at the planet. The image was taken at 19:56 UTC (21:56 CEST) by the Mercury Transfer Module’s monitoring camera 3, when the spacecraft was just over 4000 km from the planet’s surface. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

While not apparent in these flyby images, the nature of the dark material associated with Manley Crater and elsewhere will be explored further by BepiColombo from orbit. It will seek to measure just how much carbon it contains and what minerals are associated with it, in order to learn more about Mercury’s geological history.

Annotated version of the image above. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

Snaking scarps

In the two closest images one of the most spectacular geological thrust systems on the planet can be seen close to the terminator of the planet, just to the bottom right of the spacecraft’s antenna. The escarpment, called Beagle Rupes, is an example of one of Mercury’s many lobate scarps, tectonic features that probably formed as a result of the planet cooling and contracting, causing its surface to become wrinkled like a drying-out apple.

Beagle Rupes was first seen by NASA’s Messenger mission during its initial flyby of the planet in January 2008. It is about 600 km in total length, and cuts through a distinctive elongated crater named Sveinsdóttir.

Beagle Rupes bounds a slab of Mercury’s crust that has been thrust westwards by at least 2 km over the adjacent terrain. The scarp curves back at each end more strongly than most other examples on Mercury.

Key moments during BepiColombo’s third Mercury flyby on June 19, 2023. The ESA/JAXA spacecraft will pass the surface of the planet at a distance of about 236 km +/- 5 km. Credit: ESA

In addition, many nearby impact basins have been flooded by volcanic lavas, making this a fascinating region for follow-up studies by BepiColombo.

The complexity of the topography is well displayed, with shadows accentuated close to the day-nightside boundary, providing a feeling for the heights and depths of the various features.

Members of the BepiColombo imaging team are already having a lively debate about the relative influences of volcanism and tectonism shaping this region.

“This is an incredible region for studying Mercury’s tectonic history,” says Valentina Galluzzi of Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). “The complex interplay between these escarpments shows us that as the planet cooled and contracted it caused the surface crust to slip and slide, creating a variety of curious features that we will follow up in more detail once in orbit.”

Farewell ‘hugs’

As BepiColombo moved farther from the planet it appears to nestle between the spacecraft’s antenna and body from the perspective seen in these images. A ‘farewell Mercury’ sequence of images was also taken from afar as BepiColombo receded from the planet; these will be downloaded tonight.

BepiColombo appears to ‘hug’ Mercury in this image taken by the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission on June 19, 2023, as the spacecraft sped by for its third of three gravity assist maneuvers at the planet. The image was taken at 20:29 UT (22:29 CEST) by the Mercury Transfer Module’s monitoring camera 3, when the spacecraft was 11,780 km from the planet’s surface. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

In addition to images, numerous science instruments were switched on and operating during the flyby, sensing the magnetic, plasma and particle environment around the spacecraft, from locations not normally accessible during an orbital mission.

“Mercury’s heavily cratered surface records a 4.6 billion year history of asteroid and comet bombardment, which together with unique tectonic and volcanic curiosities will help scientists unlock the secrets of the planet’s place in Solar System evolution,” says ESA research fellow and planetary scientist Jack Wright, also a member of the BepiColombo MCAM imaging team.

Annotated version of the image above. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

“The snapshots seen during this flyby, MCAM’s best yet, set the stage for an exciting mission ahead for BepiColombo. With the full complement of science instruments, we will explore all aspects of mysterious Mercury from its core to surface processes, magnetic field, and exosphere, to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its parent star.”

What’s next?

BepiColombo’s next Mercury flyby will take place on 5 September 2024, but there is plenty of work to occupy the teams in the meantime.

The mission will soon enter a very challenging part of its journey, gradually increasing the use of solar electric propulsion through additional propulsion periods called ‘thrust arcs’ to continually brake against the enormous gravitational pull of the Sun. These thrust arcs can last from a few days up to two months, with the longer arcs interrupted periodically for navigation and maneuver optimization.

Timeline of flybys during BepiColombo’s 7.2-year journey to Mercury. Credit: ESA

The next arc sequence will start in early August and last for about six weeks.

“We are already working intensively on preparing for this long thruster arc, increasing communications and commanding opportunities between the spacecraft and ground stations, to ensure a fast turnaround between thruster outages during each sequence,” says Santa Martinez Sanmartin, ESA’s BepiColombo mission manager.

After a seven-year journey through the inner Solar System, BepiColombo will arrive at Mercury. While still on the approach to Mercury, the transfer module will separate and the two science orbiters, still together, will be captured into a polar orbit around the planet. Their altitude will be adjusted using MPO’s thrusters until MMO’s desired elliptical polar orbit is reached. Then MPO will separate and descend to its own orbit using its thrusters. The fine-tuning of the orbits is then expected to take three months, after which, the main science mission will begin. Credit: ESA

“This will become more critical as we enter the final stage of the cruise phase because the frequency and duration of the thrust arcs will increase significantly – it will be almost continuous during 2025 – and it is essential to keep on course as accurately as possible.”

BepiColombo’s Mercury Transfer Module will complete over 15,000 hours of solar electric propulsion operations over its lifetime, which together with nine planetary flybys in total – one at Earth, two at Venus, and six at Mercury – will guide the spacecraft towards Mercury orbit. The ESA-led Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the JAXA-led Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter modules will separate into complementary orbits around the planet, and their main science mission will begin in early 2026.

“Typical beer advocate. Future teen idol. Unapologetic tv practitioner. Music trailblazer.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

How did black holes get so big and so fast? The answer lies in the darkness

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin