In 1964, paleontologists discovered the skull of a giant salmon ancestor in a quarry near the town of Gateway, Oregon. Some estimate that the salmon grew to a length of nine feet, making it the largest known salmon — a family of more than 200 species of fish that includes all species of salmon, trout and taimen — to ever swim on land. Paleontologists who discovered the fossils discovered a huge tooth on either side of the salmon's jaw. These teeth were drilled near the skull but not attached to it, so paleontologists guessed that the salmon's tusks were curved downward like those of saber-toothed tigers in the genus. SmilodonWhich prompted them to dub the genres Smilodonichthys rastrosus (It will be renamed later Onchorinchus rastrosus). These reconstructions have earned the fish its tough nickname, the saber-tooth salmon, and salmon have tangled their teeth in reconstructions for decades.

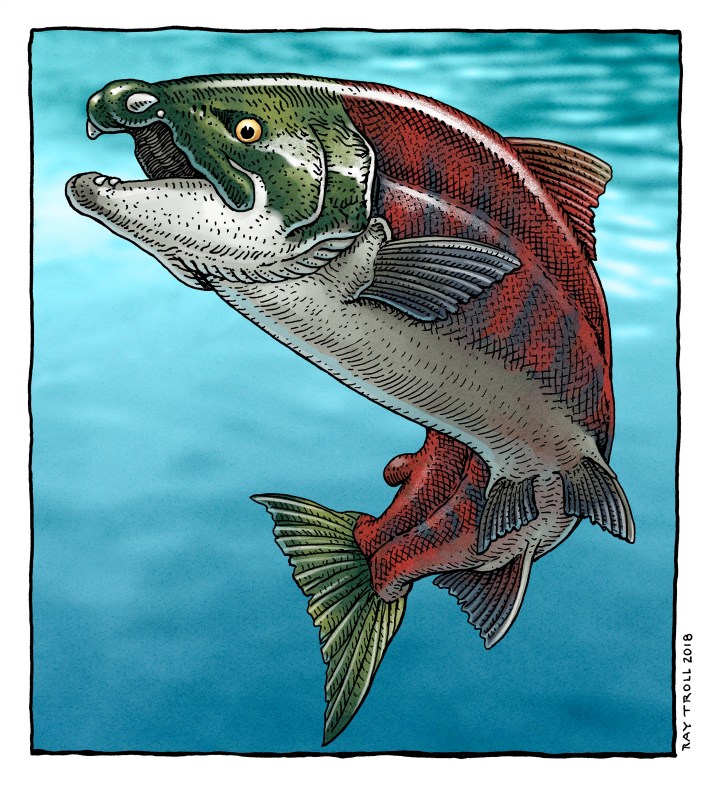

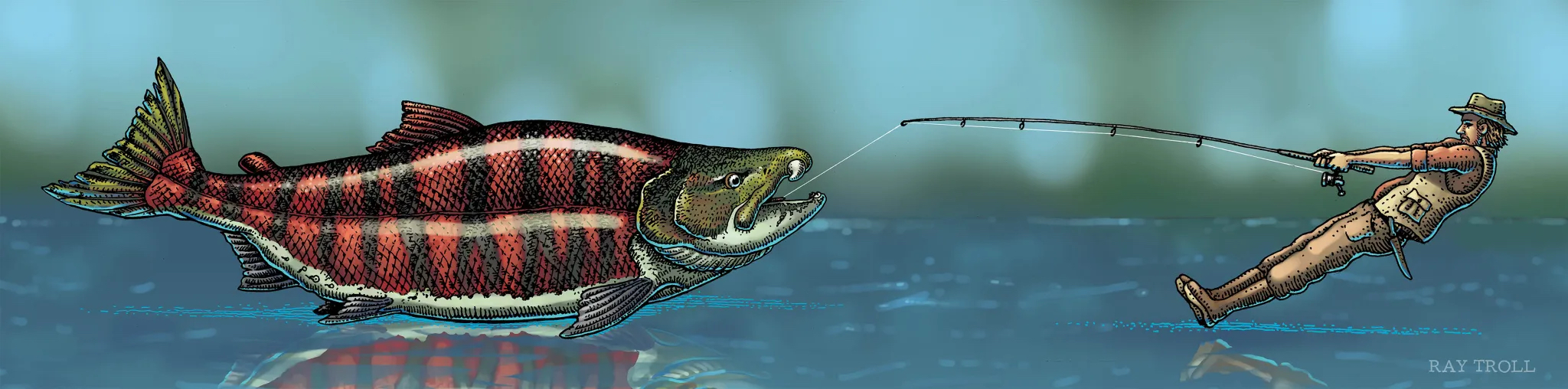

In 1990, artist Ray Trull had a question. “I was wondering if trout and salmon really existed in the days of the dinosaurs,” he wrote in an email. He contacted scientists at the University of Washington and asked whether salmon lived during the Cretaceous period. “I remember someone said, ‘No, but have you heard about giant prehistoric salmon?’” Trull said. When scientists sent him a paper describing it Oh Rastrosus“I just went crazy,” Trull said. “It was too good to be true…it almost seemed like a joke.” Fish have been his muse since he moved to Alaska near a salmon stream, and began drawing sabertooth salmon, eventually traveling to the University of Oregon in Eugene to see the overall style. “They let me take it out on the sidewalk where I drew its size in chalk,” he said.

More than two decades later, Trull painted a mural of sabre-toothed salmon at the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History, where the salmon bared their teeth alongside saber-toothed tigers. Two months later, he learned that paleontologists had just discovered two new, better-preserved salmon skulls: this time, the larger fish's teeth were attached. But they did not point downward like the fangs of the cat of the same name, but rather protruded outward like the fangs of a pig or wild boar. com. mutjac. A group of researchers including Troll describe these new fossils and the salmon's updated face in a new paper One plus.

When researchers realized that the saber-toothed salmon no longer had saber teeth, they banded together to find a new name for the ancient creature. They compiled a shortlist and discussed options. “Will it be fangs? Will it be horns?” said Keren Clayson, a paleontologist and anatomist at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine and author of the new paper. Troll had a clear favorite: toothed salmon. “It rolls off the tongue a lot easier than some of the other ideas that are being thrown around and it seems to describe teeth well,” Trull said. Clayson said the team agreed “to honor someone who draws salmon with such skill and such joy.”

Scientists have known about the existence of these two new specimens for several years, but a dangerous rocky outcrop prevented them from collecting them. But by 2014, the overhang had eroded enough that they could excavate the fossils and prepare them for the museum. The two fish were petrified while in contact with each other, and the authors carefully separated them into sections for CT scans. But the salmon's new face was clearly visible before it entered the machine. “It looks like this fish is smiling at you, and there are these big teeth facing outward,” Clayson said.

But fish jaws are not as stable as human jaws. Our teeth are attached to our jaw bones, which we move to chew our food. “There are some groups of fish that can actually push their mouths out quite far to be able to catch the prey they want,” Clayson said. The teeth of these fishes and their jaws are loosely attached to tissue, making them much easier to dislodge or separate during the fossilization process. “We were trying to find out whether the hypothesis was correct or not,” Clayson said. “Were they supposed to be in a downward position? Were we looking at something that might have been deformed during fossilization?”

CT scans allowed Clayson to digitally dissect the two skulls and discern which parts of the fossil were bone, rock or other tissue. Once she removed the rock from the scans and looked at each bone individually, she was able to see different pieces of tissue that point or protrude in certain ways and understand how they relate to the bone. This tissue, which had eroded and disappeared in salmon fossils found in 1964, proved that the giant teeth had fossilized as they appeared in life. When Clayson saw the internal anatomy through the scans, she remembers thinking, “Yes, this is how it should be.”

The two new salmon fossils were found touching each other inside the rock, which Clayson believes means they were fossilized at the same time. The presence of multiple salmon fossils in the area suggests they were all buried quickly and buried during the reproductive process, she said. “It probably wasn't quite as dramatic as what happened to the people of Pompeii who were all covered in ash,” Clayson said. “But it's like this.”

Characteristics of the skulls and teeth in the two fossils reveal that the salmon were male and female, perhaps a mating pair. When modern salmon migrate from the sea to rivers and streams to spawn, their skulls deform to increase the odds of mating. Male sockeye salmon develop a convex back and a hook in their jaws called a “kip,” and their jaws actually lengthen. “They always remind me a little bit of Gonzo from the Muppets,” Clayson said. Female salmon dig nests in the gravel called reds, and when the nest is complete, the two salmon swim side by side to lay eggs. “They're basically hovering next to each other,” Clayson said. “They let the egg and sperm go one at a time, and they'll mix, and then they'll nest in that nest.” Clayson believes the pair were breeding at the time they fossilized. “They are very close to each other,” she said.

2016 paper in the journal Paleobios It has been suggested that toothed salmon may have undergone similar developmental changes during their breeding season, as salmon specimens from freshwater sediments had the largest teeth with the tips of the teeth most exposed, suggesting that salmon used their tusks to defend territories and build nests for spawning. . Oh Rastrosus They did not use their spiny teeth for feeding, as their fossils reveal evidence of sieve-like gills that would have allowed the fish to feed on plankton. But the new paper speculates that toothed salmon also used their large teeth as weapons to attack or defend themselves against other fish, in addition to nest building. Many modern fish, such as sawfish, have body protrusions that can serve multiple purposes.

Clayson and his colleagues first reported the “facelift” of this famous saber-toothed salmon conference in 2016, leading to some revisions in the fish's many modern incarnations. Sculptor Gary Stapp Hacksaw He cut the saber teeth into the six-foot-tall salmon statue and reattached them to either side of the salmon's head. In the same museum, the Troll's salmon mural remains unchanged. “It's up to the museum staff to decide that, but I think the idea is to leave it as is to reflect how science changes as new discoveries emerge,” Trull said. “It reflects our understanding at the time.” So the Troll's saber-toothed salmon will still be fanged and snarling into the future, a relic of the past just like his fish muse.

“Typical beer advocate. Future teen idol. Unapologetic tv practitioner. Music trailblazer.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

How did black holes get so big and so fast? The answer lies in the darkness

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin