A large granite formation discovered under an ancient lunar volcano is further evidence that the far side of the Moon was once glowed by volcanic eruptions.

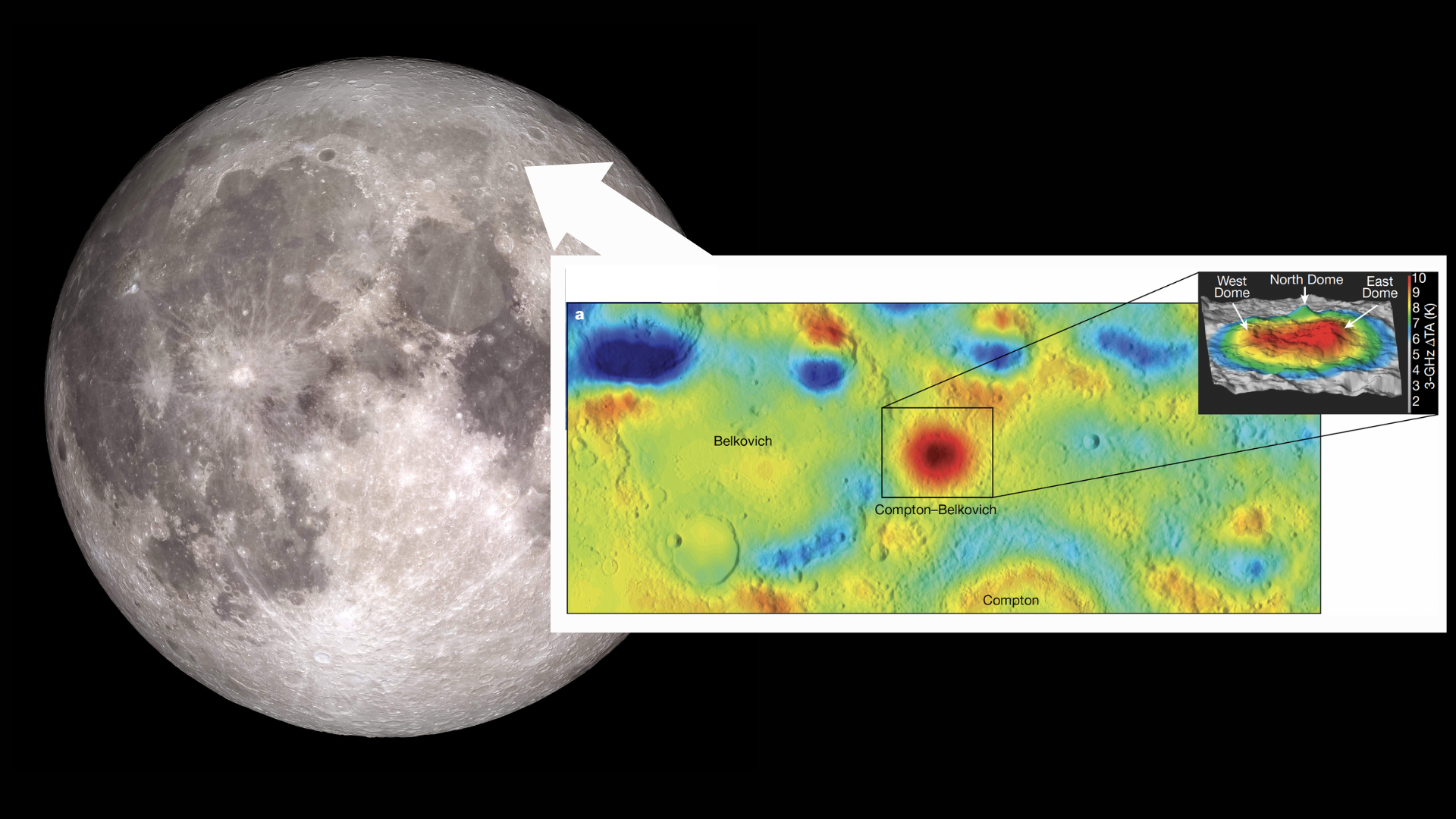

The granite has been found under a suspected volcanic feature on the Moon called the Compton-Belkovichi. This feature likely formed as a result of cooling magma that fed fiery eruptions of lunar volcanoes about 3.5 billion years ago.

Finding remnants of volcanic activity in this region of the Moon isn’t entirely unexpected, as researchers have long suspected that this region is an ancient complex of volcanoes. What was surprising to the team, however, was the size of this patch of cooled magma, estimated to be about 31 miles (50 kilometers) across. The discovery of this large body of granite beneath the Compton-Bilkovitch volcanic complex could help scientists explain how the lunar crust formed in the early lunar history.

Related: Space Volcanoes: Origins, Variables, and Eruptions

The granite object was discovered by a team of scientists led by Planetary Science Institute researcher Matthew Siegler using data collected by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. The data produced by the orbiter allowed the team to measure temperatures below the Compton-Belkovitch surface. The data showed that heat is being generated which can only come from radioactive elements that are found only on the Moon such as granite – an igneous rock found in volcanic “plumbing” as “Batholith”, which are underground rock formations created when magma cools without erupting.

“Any large body of granite that we find on Earth used to feed a large group of volcanoes, such as a large system that feeds the Cascade volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest today,” Siegler said. he said in a statement. “Batholiths are much larger than surface-feeding volcanoes. For example, the Sierra Nevada Mountains are a basin of volcanic rock, left over from a volcanic chain in the western United States that has been around for a long time.”

The formation of granite on Earth is usually the result of water and plate tectonics creating large areas of molten rock called magmas below the surface of our planet. Although common on Earth, granite is much rarer on the Moon as a result of the absence of both water and plate tectonics. This means that this finding could indicate conditions that existed locally or globally on the moon when it was hosting volcanic activity.

“If you don’t have water, making granite requires tough situations,” Siegler said. “So, this system has no water and no plate tectonics—but you have granite. Was there water on the Moon—at least in this one spot? Or was it particularly hot?”

Siegler will present the team’s research at the Goldschmidt Conference, in Lyon, France, between July 9 and 14. The team’s findings are also discussed in a paper published July 5 in the journal Nature.

“Typical beer advocate. Future teen idol. Unapologetic tv practitioner. Music trailblazer.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

How did black holes get so big and so fast? The answer lies in the darkness

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin