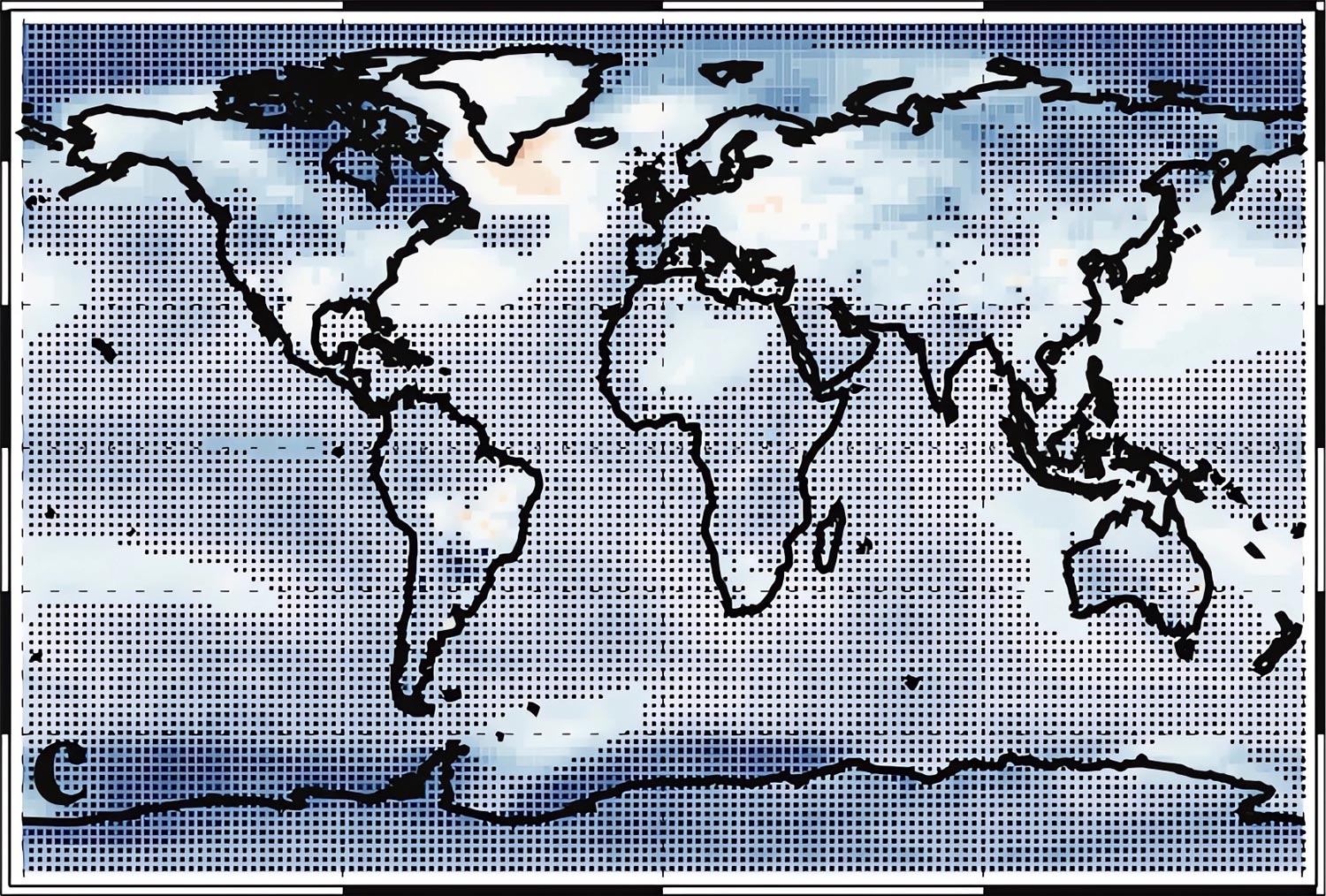

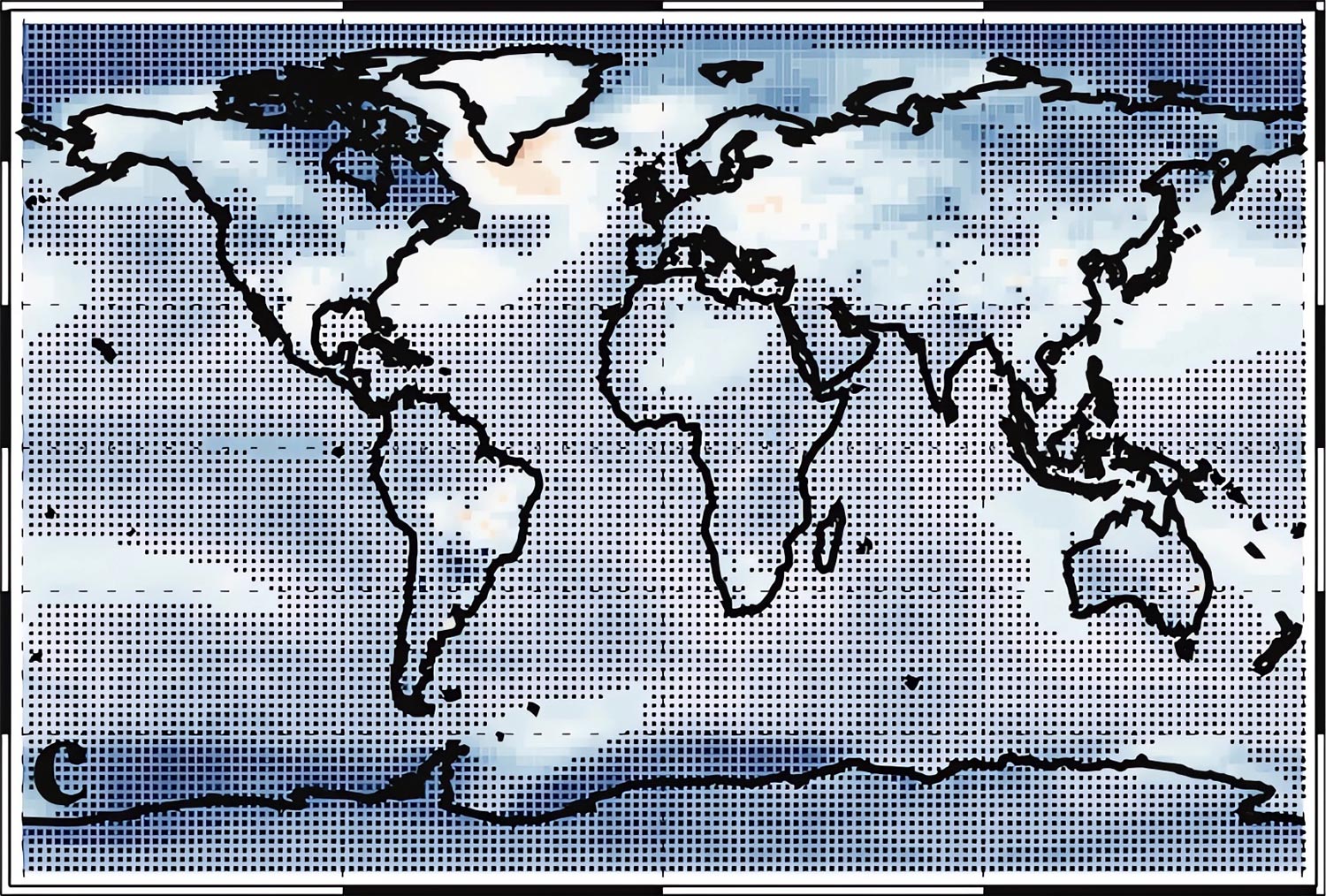

Average near-surface air temperature response to methane, decays to shortwave effects only. Credit: Robert Allen/UCR

Strong greenhouse gas effects: slightly less than previously thought.

UC Riverside researchers found that methane not only traps heat in the atmosphere, but also creates cold clouds that offset 30% of the heat. Methane absorption of shortwave energy reversibly causes a cooling effect and reduces the precipitation increase by 60%. This result underscores the need to incorporate all known effects of greenhouse gases into climate models.

Most climate models don’t account for the new University of California, Riverside finding: methane traps a great deal of heat in Earth’s atmosphere, but it also creates cold clouds that offset 30% of the heat.

Greenhouse gases such as methane create a kind of blanket in the atmosphere, trapping heat from Earth’s surface, called longwave energy, and preventing it from emitting into space. This makes the planet hotter.

“The blanket doesn’t generate heat unless it’s electric. You feel warm because the blanket blocks your body’s ability to send its heat into the air. It’s the same concept,” explained Robert Allen, UCSD assistant professor of geosciences.

In addition to absorbing longwave energy, it turns out that methane also absorbs energy from the sun, known as shortwave energy. “This should warm the planet,” said Allen, who led the research project. “But contrary to what was expected, the absorption of short waves encourages changes in clouds that have a slight cooling effect.”

Average near-surface air temperature response to methane, a decomposer to (a) longwave and shortwave effects; (b) long wave effects only; and (c) only short wave effects. Credit: Robert Allen/UCR

This effect is detailed in the journal NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Methane changes this equation. By holding on to energy from the sun, methane is introducing heat the atmosphere no longer needs to get from precipitation.

Additionally, methane shortwave absorption decreases the amount of solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface. This in turn reduces the amount of water that evaporates. Generally, precipitation and evaporation are equal, so a decrease in evaporation leads to a decrease in precipitation.

“This has implications for understanding in more detail how methane and perhaps other greenhouses gases can impact the climate system,” Allen said. “Shortwave absorption softens the overall warming and rain-increasing effects but does not eradicate them at all.”

The research team discovered these findings by creating detailed computer models simulating both longwave and shortwave methane effects. Going forward, they would like to conduct additional experiments to learn how different concentrations of methane would impact the climate.

Scientific interest in methane has increased in recent years as levels of emissions have increased. Much comes from industrial sources, as well as from agricultural activities and landfill. Methane emissions are also likely to increase as frozen ground underlying the Arctic begins to thaw.

“It’s become a major concern,” said Xueying Zhao, UCR Earth and planetary sciences Ph.D. student and study co-author. “We need to better understand the effects all this methane will bring us by incorporating all known effects into our climate models.”

Kramer echoes the need for further study. “We’re good at measuring the concentration of greenhouse gases like methane in the atmosphere. Now the goal is to say with as much confidence as possible what those numbers mean to us. Work like this gets us toward that goal,” he said.

Reference: “Surface warming and wetting due to methane’s long-wave radiative effects muted by short-wave absorption” by Robert J. Allen, Xueying Zhao, Cynthia A. Randles, Ryan J. Kramer, Bjørn H. Samset and Christopher J. Smith, 16 March 2023, Nature Geoscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41561-023-01144-z

“Typical beer advocate. Future teen idol. Unapologetic tv practitioner. Music trailblazer.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

How did black holes get so big and so fast? The answer lies in the darkness

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin